Blog & News

Stay up to date in the QA world.

Just Rebuild It – Tales from the Trek – Understanding Existing Functionality

On projects that replace existing systems, project sponsors have often insisted that we didn’t need any business analysis because the existing system was “fully documented” in the form of the old system. I wrote about one problem with that mindset, which is that the new system will have all the issues that the old system had.

Another problem is that it takes a lot of time to figure out how the existing system work. The development team will end up taking time to analyze the existing system regardless of whether analysis time is in the budget or not. Contrary to what project sponsors often believe, users of the system don’t know all the details of how a system works, and code is not “self-documenting”.

Multiple Users

Most complex systems have a variety of users. A relatively simple sales system has different users who place orders, manage orders, ship orders, manage the financials of the orders, report on orders, manage inventory, and handle returns. It’s time consuming for an analyst to research, understand, and record how all the parts of the system work from the users’ points of view.

User Knowledge is the Tip of the Iceberg

Even after talking to all the users, an analyst won’t know the full functionality of the system. In my experience, it’s rare to find users who know the details of every calculation, decision, workflow, and automated interface the system has behind the scenes. In the few cases where I’ve found that a system was well documented, I’ve been told that the documentation was outdated, so I couldn’t trust it.

Why not Just Look at the Code?

I’ve had project sponsors ask why the developers can’t just look at the code and rebuild the same system in a new technology. They assume that the rebuild is almost a copy and paste of the existing code. Although code examination is one of the techniques for understanding an existing system, developers are not able to quickly reverse engineer functionality from code in a complex system, even if the code is well organized. Any developer who’s made even a small change to a complex, unfamiliar codebase will tell you that understanding the code is time consuming.

Interviewing users, reviewing the exitisting user interface, and reviewing the existing code base are all important ways to understand the existing sytem. However, these actions clearly take time, and need to be budgeted for.

Feedback

What challenges have you had getting budget approved for business analysis? What have you done to address those challenges? I’d love to hear your tales from the trek.

Just Rebuild It – Tales from the Trek – We Don’t Need Requirements

Technology Upgrades – Self Documenting (?)

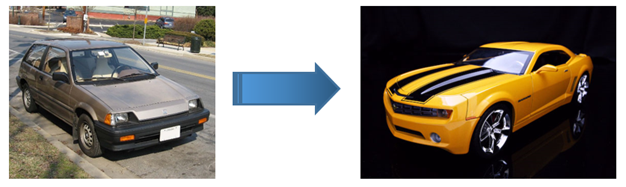

I’ve been on several projects where the goal is to replace an existing, mature system with a brand new system in a new technology. This is generally a huge investment in time and money, fraught with risk, and results in almost the same functionality. Still, it can be necessary due to the old software being dependent on unsupported or non-secure technology and exponentially increasing maintenance costs. In a way, it’s like making the decision to replace an old car rather than repair it.

On nearly every project of this type that I have experienced, the project sponsors have insisted that we could cut out, or at least drastically reduce, business analysis. Their reasoning was that because the new system simply had to work exactly like the old system, the new system was already “fully documented” in the form of the old system.

There are a number of reasons why assuming that the old system “fully documents” the new system is a mistake. I’ll address one of them here.

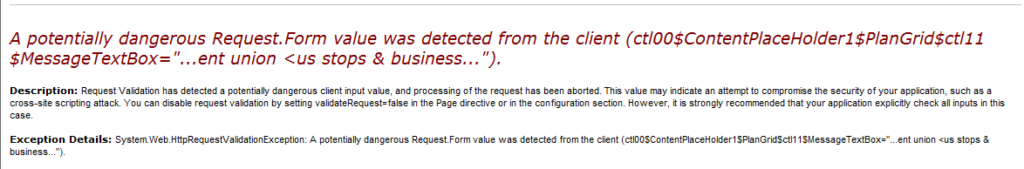

Rebuilding Bugs and Poor Functionality

Often, software that’s running on outdated, unsupported technology has a lot of bugs and poor functionality that haven’t been addressed. Any changes to the system have become risky because the system is so fragile. If the only direction given to the development team is to rebuild the existing system as is with no additional analysis, the team will literally be building the same bugs and functionality into the new system. There’s no good way for the development team to know if something should be changed without at least some investment in business analysis.

The end result is that the users and project sponsors are even more frustrated with their investment in new software only to end up with the same problems. Even worse, sometimes, building the bugs into the new system costs more money. Imagine how much more it would cost to try to literally rebuild an old car exactly as it is rather than build a new car with the same basic functionality. It would take effort to make the brakes squeak just like the old car, have it shake at high speeds just like the old car, and randomly stall in the middle of intersections just like the old car.

The money spent rebuilding old bugs would be much better spent on some business analysis.

Feedback

What challenges have you had with generating requirements when replacing existing systems? What actions have you tried to address the challenges? I’d love to hear your stories from the trek.

Setting Expectations – Lessons From a Little League Umpire

I’ve found through the years that projects go more smoothly when expectations are set at the beginning. Whether I’m in a Business Analyst or Quality Assurance role, I’ve found that the project goes more smoothly when the processes are laid out clearly up-front and the known limitations of the project are called out and addressed before the project starts. When people are not aware of the time that they need to dedicate to the project or the limits of the project scope until the project is well underway, they can get quite upset.

My most memorable lesson on the importance of setting expectations is still the one I learned while umpiring little league in high school.

Strike One!

I umpired my first game when I was 14 years old. The league was a city-run little league program, and some of the divisions had kids as old as me. Other than watching a lot of baseball, the only preparation the city gave me was handing me an armful of equipment and a copy of the rulebook. I read the rulebook several times and felt that I was as ready as I could be.

I set up the bases and put on my equipment for the first game. I said hi to the two managers and nervously took my spot behind the plate. My calls were a little shaky, but I was surviving. Surviving until the third batter, that is.

I lost my concentration on a pitch and uncertainly called, “Strike?” The batter’s manager yelled at me, “How can that be a strike?!? It hit the dirt before it even crossed the plate!”

I sheepishly said, “It did? I guess it was a ball then.”

Needless to say, the managers, players, and parents argued with me vehemently on nearly every call after that. I wasn’t sure I’d ever want umpire another game. However, the manager of the umpires was desperate for warm bodies to call the games and convinced me to finish out the season. I never had a game as bad as the first one, but every game was stressful and the managers, parents, and players argued with me regularly.

Year Two – Setting Expectations

In the next year, I read a book called “Strike Two” by former Major League umpire Ron Luciano. His stories about handling some of the toughest personalities in baseball gave me the insight and confidence that I needed to try umpiring again. The difference this year was that I was going to set some expectations before every game.

I met with both managers before every game and explained the following:

- I’m the only umpire, and I only see each play once. Don’t bother arguing any judgment call such as ball vs strike or safe vs out. I won’t change my call.

- I call a big strike zone. If any part of the ball is over any part of the plate from the top of the batter’s shoulders to the bottom of their knees, I’m calling it a strike.

- I’m not a professional umpire. I may make an error in the rules. If either manager believes that I made an error in the rules, let me know. I will call a time-out and meet with both managers to review the rule book and make an adjustment to the call if warranted.

Taking the time to set these expectations made a huge difference in my ability to manage the game. The managers would tell their players that I have a big strike zone and that arguing with me was pointless. The players swung a lot more, put the ball in play a lot more, and I got very few arguments.

In addition, after the games, parents would tell me that it was one of the best games they went to all year, especially for the younger age groups. Apparently, in many other games, the batters for each team would simply draw walks until they reached the 10-run mercy rule for the inning. This was boring for everyone involved. Because players were swinging more when I umpired, the ball was put into play more, and the kids and parents had a lot more fun.

Your Experiences

I’d like to hear about your experiences with setting expectations. Have you found that setting expectations up front helps your projects? Have you received any resistance to setting expectations at the start of a project?

Influencers – Jayme Edwards

There are a number of blogs that I enjoy reading about all areas of the software development process. The software development process includes project management, business analysis, development, and testing, of course. In addition, delivering software that works requires consideration of concepts around management, sales, and business organization.

I’d like to share some of the blogs that I find influential when thinking about how to build software that works.

Jayme Edwards – Consulting and Continuous Delivery Expert

Jayme Edwards is someone who I’ve known for a while. We’ve had many great discussions over the years about consulting and continuous delivery. I’ve gained a lot of insight from him directly and from his blog posts.

One blog post that recently resonated with me was titled Establishing Trust to Make IT Development Process Changes. His points about authenticity and setting realistic expectations up front are keys to a successful client/consultant relationship. In addition, he referenced Peter Block’s Book, Flawless Consulting which lays out three roles that a consultant can have when interacting with a customer: Expert, Pair of Hands, or Collaborator. I have been in all three roles, and although I enjoy them all, I especially enjoy working with a client in the Collaborator role.

Jayme Edwards’s is also incredibly knowledgeable in the area of Continuous Delivery. He is intimately familiar with the theory of Continuous Delivery. More importantly, I have seen him successfully move multiple clients into a successful Continuous Delivery model. Because Jayme Edwards has put the theory into practice many times, I find his posts on the topic to be particularly insightful and credible. If you’re interested in learning about Continuous Delivery, you should check out his posts.

Feedback

What do you think of Jayme Edwards’s blog and the concepts he writes about? What blogs and resources do you find particularly interesting and useful for building software that works?