Category: Quality Software

Metric Misuse – Quality Assurance Metrics Gone Awry

I was reading through some posts from Bob Sutton, one of my favorite management gurus, and I ran across a post that contains one of my favorite Dilbert comic strips.

Bob Sutton’s post, as well as the comments that I made on his blog, reminded me of one of my favorite topics: misused Quality Assurance metrics.

Tying Quality Assurance Metrics to Financial Rewards – A Dangerous Game

“Treat monetary rewards like explosives, because they will have a powerful impact whether you intend it or not.” –Mary and Tom Poppendieck, authors of Implementing Lean Software Development: From Concept to Cash

Over the years, many people have asked me what Quality Assurance metrics they should use to evaluate employee performance. My advice is that Quality Assurance metrics should not be used directly to evaluate employee performance. The Dilbert comic strip may seem a bit extreme, but it’s exactly what happens when employee performance is based strictly on metrics. This is true regardless of whether monetary rewards are explicitly tied to the metrics or not.

In my comments on Bob Sutton’s blog, I mentioned three specific metrics that had unintended effects when used for evaluating employee performance:

- rewarding testers for the number of test cases they wrote resulted in poorly written test cases;

- rewarding testers for the number of bugs they found resulted in a high number of unimportant or duplicate bugs reported; and

- penalizing testers for bugs rejected by the test lead or development staff resulted in important bugs going unreported.

Many people think that they have the ability to write a set of metrics that can be used to unequivocally gauge the performance of a Quality Assurance professional, but I have not yet encountered a metric that couldn’t be manipulated to favor the employees.

(If the metric can’t be gamed, it probably isn’t under the control of the employees, so it wouldn’t be effective at driving behavior anyhow.)

Are Metrics Worthless Then?

Actually, metrics are a great tool for identifying coaching opportunities and potential problems. However, in order to get honest metrics, they shouldn’t be used directly for employee evaluations or employee rewards.

When I’ve looked at the metrics that I mentioned earlier with an eye towards coaching, I had excellent results.

- Reviewing the number of test cases written helped me identify a tester on my team who was putting much more detail than I wanted into his test cases. After some coaching, he was able to consistently meet my expectations.

- Reviewing the number of bugs found by each tester helped me identify a tester who was digging into the root cause of the most difficult to reproduce bugs. She didn’t report as many bugs as others, but her work was critical to getting a great product out the door in a timely manner. It turned out that she was the most skilled tester even though she reported the fewest bugs.

- Reviewing the number of bugs rejected by the development staff helped me identify a manager who was evaluating his programmers based solely on the number of valid bugs found in their code. The developers were motivated to simply mark bugs as invalid rather than fix the bugs. This insight allowed me to address the problem directly with that manager.

Good Quality Assurance metrics provide powerful tools for managing a Quality Assurance team when used properly. However, they shouldn’t be used in a vacuum. They should just be considered one data point among many.

I was only able to scratch the surface of this topic in this blog post. I plan to discuss specific metrics in future blog posts. In the meantime, if you want to read a much more in-depth review of the pros and cons of employee incentives, you can find one paper here.

Your Experiences

I know that a lot of people feel passionately about Quality Assurance metrics, both pro and con. I’m very interested to hear about your experiences with Quality Assurance metrics. Have you found any that were particularly useful? Have you found any that had unintended consequences?

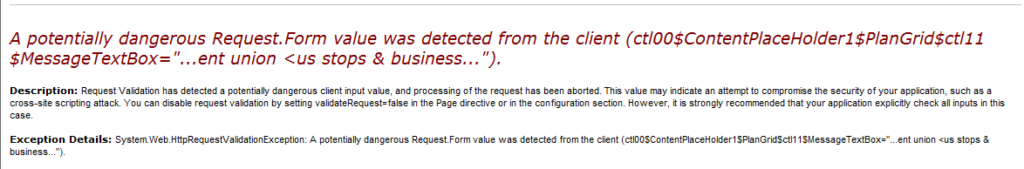

Communication – Tales from the Trek – Perception is Reality

Based on my conversations, I believe that most people perceive that they do more work than others. It seems common that all members of a household think they do more than their fair share of work, and most members of teams at work feel the same way. I believe that a big driver in this perception is that people know exactly what work they’ve done, but they are not aware of the work that others have done.

IT is Lazy!

At one place where I worked, the business side of the department often expressed to me that IT was lazy. They said that IT was never getting to any of their requests, and they weren’t sure what IT was doing all day. Not surprisingly, the IT department expressed that they were overworked and accomplishing a lot. Why was there this extreme difference in perception?

The IT department met with the business leadership each year to determine the priorities for the year based on the hours budgeted. IT was excellent at delivering on the priorities; however, the business had many more requests for changes and improvements that were above and beyond the priorities for the year. So, most individuals on the business side didn’t have their personal priorities addressed even though the overall strategic priorities for IT were accomplished.

Changing Perceptions

A director of the IT department came up with an idea that was very simple but incredibly effective. He created a giant checklist of the scheduled IT projects and posted them in a few prominent places around the office. As each project was completed, he put a checkmark next to the item.

The comments that I heard from the business completely changed. Although their personal priorities may not have been addressed, they could see the importance of the priorities posted on the checklist. In addition, they could see clearly the progress that had been made. The checklist had greatly improved the business’s perception of IT.

Feedback

What perception challenges have you faced? How did you address the challenges? I’d love to hear your tales from the trek.

Value of QA – People Do Not Find Their Own Errors

I’ve noticed, through the years, that people often dismiss the need for Quality Assurance by saying, “These are good developers. We don’t need to test their code.”

Of course, anyone in testing knows from experience that even the best developers have errors in their code. I’ve also found that it seems easier for me to see errors in other people’s work than in my own.

It turns out that I’m not the only one who experiences that phenomenon. According to this blog post by Dorothy Graham, some research shows that people tend to find only about 1/3 of their own errors on initial inspection.

That’s a powerful justification for an investment in Quality Assurance.

Are you familiar with this research or statistic? I’m planning to look more into Capers Jones’ research and see how it applies to the value of Quality Assurance.

Prioritization and Quality – Tales from the Trek – The Hoarders

Impact of Prioritization on Quality

As I’ve mentioned before, a key aspect of building quality software is ensuring that it does what the users need it to do. In my experience, the backlog of feature request (whether written or held in the stakeholders’ heads) is always much larger than what the development team can build in a short period of time.

When the backlog gets too big, people could spend more time managing the backlog than actually building anything. What is more likely, though, is that most of the backlog is ignored, and the clutter causes great ideas to get lost. I have seen cases where key customer issues ended up unaddressed for months until the customer complained a third or fourth time.

Idea Hoarding

I sat down with one of my clients to look at their backlog, and we found that they had over 400 backlog items that had not even been viewed for more than a year. They had more new, high-priority work coming in than they could deliver, so their backlog was growing. Clearly, nobody was ever going to review, let alone work on, the items that were over a year old. I suggested simply closing the backlog items that hadn’t been touched for over a year, but the client didn’t want to remove any items from the backlog without first reviewing them in a meeting with a team of key people, which was not going to happen.

The discussion reminded me of an episode of Hoarders where they were trying to convince someone to sell most of his 27 tool boxes. He agreed that 27 might be overkill, but he still didn’t want to sell them and insisted that the average person, who wasn’t a handyman like him, would need at least 7 toolboxes.

Time to Declutter

When a backlog gets hopelessly large, you may want to consider declaring backlog bankruptcy (based on the concept of email bankruptcy) and simply close all items that haven’t been looked at in over a year. If that sounds scary, I can understand. I tend towards hoarding myself, and I hate the thought of getting rid of something that might come in handy later. If declaring backlog bankruptcy, it may help to keep these ideas in mind:

- When there are too many backlog items, they are all ignored. The best ideas can’t break through the clutter.

- Business changes so quickly that most ideas more than a year old aren’t relevant any more.

- If an idea in the backlog is truly that important, it will get entered as a new entry again. In fact, if it’s that important, it probably was entered multiple times and has already been implemented.

- You can always search on closed items if you really, really want to!

Keeping the Backlog Under Control

Once you cleaned up the backlog, you want to try to keep it manageable. It helps to have a weekly triage process where the items are reviewed and prioritized. Some decisions that should be made during the triage process are:

- Is there any realistic chance this item will get resources in the next year? If not, close it.

- If the item is going to remain open, assign it to an owner who will take responsibility for getting the item onto the schedule.

- Enter the date the issue was last reviewed.

- Assign a priority and effort to the item.

I’ve found that it’s easier to identify which issues to review if you create a report that shows the priority of each item, the date it was entered, and the date it was last reviewed. This type of report helps ensure that older items are addressed.

Feedback

What challenges have you had with backlog clutter? What actions have you tried to address the challenges? I’d love to hear your stories from the trek.